Inside this 'virtual reality arena,' Stellantis aims to build a better car factory

Published in Business News

AUBURN HILLS, Michigan — Deep inside the sprawling Chrysler Technology Center is a metal structure equipped with sensors that Stellantis NV engineers call their "virtual reality arena."

Stepping into this VR laboratory, the engineers don headsets, pick up controllers, and are virtually transported to an assembly line inside any one of the automaker's North American production facilities.

They can simulate what it's like to attach the doors to a Toledo-made Jeep Wrangler SUV, or connect wiring on the underbody of a Sterling Heights-built Ram 1500 pickup.

The purpose behind the lab is to improve the automaker's existing assembly lines and help design new factories, specialists said in a Thursday demonstration. In virtual reality, engineers can try out out ergonomic or efficiency improvements, they said, or mock up how to install new equipment at an employee's workstation.

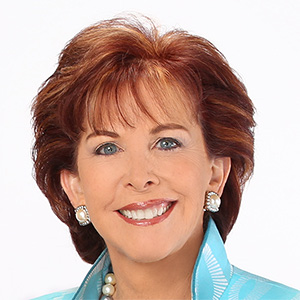

"It's very costly to shut down an assembly plant — we never want to do that; we're not making products for our customers," said Keenan O'Brien, head of the automaker's Process Engineering Center. "So doing as much as we can in the digital world beforehand shortens that period in which we have to rely on physical trials and prototypes to get things up and running."

The virtual reality room opened in 2018 and has been continually updated with better software and equipment. Several trackers mounted on the metal frame trace the movements of the person working below on the "assembly line."

Stellantis has created digital mock-ups of all of its North American assembly plants and simulations of most of those plants' operations, said Joe Dzwonkowski, a virtual reality design review specialist. The automaker has in recent years opened similar VR labs at several of its European and South American sites.

Even before construction began on the Detroit Assembly Complex-Mack plant that builds the Jeep Grant Cherokee more than five years ago, Dzwonkowski noted, engineers were already working inside a "digital twin" of the factory. In other instances, virtual testing helps update plants that are being converted to make new models. Those include factories switching over to make electric vehicles, which have new production processes and ergonomic concerns tied to building and installing batteries.

Other automakers are using virtual reality in similar ways, said Sam Abuelsamid, vice president of market research at communications firm Telemetry, who attended this week's Stellantis demonstration. For years, some carmakers have used it on the product design side of their operations; Abuelsamid recalled in 2016 attending a virtual walkaround of the Lucid Air electric sedan at the Los Angeles Auto Show.

But others like BMW AG and Mercedes-Benz Group AG are also using digital mock-ups to improve their manufacturing designs in similar ways as Stellantis, he said. Mercedes and chipmaker Nvidia, for instance, partnered two years ago to digitize the automaker's production processes to make better factories.

Near the Stellantis virtual reality arena is a 3D printer — another tool that the automaker has increasingly turned to in recent years to improve its manufacturing sites.

All of the company's North American assembly plants have been equipped with 3D printing capabilities over the last few years, said Don Clack, a 3D printing and mixed reality specialist. Those capabilities have continually improved, and the printers can now churn out hand tools used by workers, or parts and fixtures needed to keep the assembly line running.

"If it can fit into the 3D printer, we can design it," said Clack, who noted that the printers use a mix of carbon fiber and fiberglass to generate components with metal-like strength.

The 3D printers at each plant are helping employees respond to tricky problems. In one notable instance at Mack, a printed component helped the factory's paint shop create a cleaner two-tone paint process for the Grand Cherokee, where the dark roof needed to be crisply differentiated from the rest of the SUV's paint color. In other instances, Clack said, 3D printed parts prevented entire assembly plants from shutting down after a critical component broke down.

"We really believe in keeping those (3D printing) labs as close to production as possible, so that they understand the pain points that the plant has, and then they can be agile in their responses," he said.

©2025 www.detroitnews.com. Visit at detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments