Vanguard's first 'outsider' boss looks to innovate with AI, private investments

Published in Business News

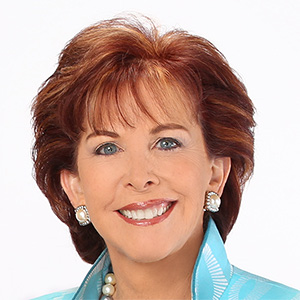

Vanguard Group has added more than $1 trillion in customer assets, from stock-market gains and new investments, since Salim Ramji was named the first outsider to run the 50-year-old, Malvern, Pennsylvania-based investment giant last year.

But that kind of growth isn’t unusual at Vanguard, which has added $7 trillion in customer assets, in the mostly rising markets of the past eight years.

Ramji is the former fund chief at BlackRock, the only investment company bigger than Vanguard. He has re-committed the company to the virtues espoused by its late founder, Jack Bogle, who favored low-fee stock-index funds and plain-talk pitches for long-term investment, which fed Vanguard’s industry-leading growth.

Ramji’s entry was smoothed by the fact the top job was split three ways: longtime director Mark Loughridge, a former IBM CFO, took over as board chairman, while Vanguard lifer Greg Davis stayed on as president.

As a private, for-profit company, nominally owned by investors but run by a self-perpetuating board, Vanguard is not required to report marketing costs, CEO pay, or other basic expenses. CEO Ramji likely earns over $20 million a year, estimates Jeff DeMaso, who edits the Independent Vanguard Adviser newsletter.

Ramji did not agree to be interviewed by The Inquirer. But, in other appearances over the past year, he’s provided insight into his approach at Vanguard, and his own evolving perception of the business.

At a conference held by the Morningstar fund data service in July, Ramji talked at length about veteran Vanguard “crew’s” “sense of idealism” and “mission.” Coming from Wall Street, he said he was skeptical at first, but his skepticism melted as he saw his new colleagues’ joy at a February round of fund fee cuts — a show of the Vanguard pro-customer ethos.

Strategy on Ramji’s watch

Vanguard and its longtime partner, stock-and-bond fund manager Wellington Management, in April announced a “strategic alliance” to sell funds “combining public and private” equities and debt, instead of just publicly traded stocks and bonds.

But no crypto, Ramji noted at the Morningstar talk: “At Vanguard we like investments that deliver cash flow” — municipal and other bonds, stocks, and “over time, if the circumstances are right, private markets.”

“We’re OK not being everything to everybody,” he added.

Vanguard has made a key move back toward traditional financial products. Ramji spotlighted Vanguard’s Cash Plus account, rolled out last year, which customers can use to pay bills and deposit checks — transactions are free — while collecting interest at about the level of a bank Certificate of Deposit.

Mortimer “Tim” Buckley, Ramji’s predecessor, had axed bank-like VanguardAdvantage accounts five years earlier. “They’ve reversed course again, in an effort to regain ‘wallet share,’ ” says DeMaso.

Some of the Bogle-believers who retired with $1 million in savings 20 years ago have lost access to a range of free or low-cost services as they spent from their accounts, inflation sapped their value, and Vanguard tightened minimums.

Ramji said he’s concerned about aging investors who could feel left behind.

Ramji called the “decumulation” of assets by aging investors “the most intractable problem in finance.” He said he’s listened into “heartbreaking” calls from retired investors ”who have adhered to all of the Vanguard principles” for decades, but now find themselves “not living the life and retirement that they should afford.”

Vanguard and its rivals, Ramji added, “really need to figure out, how do you help advise people in retirement?”

Moving Vanguard’s tech

Ramji said the company spends over twice as much on technology as it did before 2020.

He said the move from mainframe computing to “a cloud-native infrastructure,” relying in large part on Amazon Web Services, is “90% complete,” and will allow “constant improvements” to digital customer service, promising “intuitive, more customized” web applications.

In May, Ramji announced Vanguard’s “first client-facing generative AI,” a summary report synthesizing “client-ready article summaries” and “customizable synopses” of securities market research.

“We’re holding back on some of the client-facing applications — they are really good — but we want to make sure we’re doing it in a very responsible way,” without the “hallucinations” that have marred early AI applications, Ramji added at the Morningstar event.

“AI isn’t going to fix” customer service, and is unlikely to make Vanguard’s often conservative market predictions more accurate, warns Dan Wiener, founder and former head of RWA Wealth Partners, a New York investment adviser that recommends Vanguard funds.

Service gaps?

Last fall, Vanguard said it would expand its “robo-adviser” service, Digital Advisor, to anyone with as little as $100 in their account, down from the previous minimum of $3,000.

“Everyone should have access to good advice,” Ramji told the Morningstar gathering. The company is trying to boost its appeal to managers of larger private accounts, though Vanguard’s high-rated “do-it-yourself” services also compete with independent advisers.

Vanguard funds retain a powerful attraction for their clients, though Ramji has yet to make a mark like Bogle, according to a handful of area investment advisers interviewed by The Inquirer recently.

Vanguard “is a behemoth,” said Mike Horwath, chief investment officer for Diversified LLC, a $2.2 billion-asset, Wilmington-based advisory firm.

He said Vanguard has been successful retailing its popular S&P 500 Index funds and other low-fee “passive” funds, but has so far proven “less than a partner” in its efforts to sell financial planning, private funds, and other products, compared to its larger, better-funded rival, BlackRock.

“Vanguard was the first on the low-cost side,” and has forced Fidelity, Charles Schwab and other rivals to cut fees, said Robert Costello, who manages $350 million in client funds at Costello Asset Management in Huntingdon Valley.

“But there’s still gaps on the service side,” Costello added. For example, “if you have an estate (after an investor’s death), it can take two months to get rectified; it should be two weeks.”

Tax season is particularly difficult, Costello said, and Vanguard has specific paperwork requirements. “I have a client who’s pulling her hair out — she’s a crossing guard supervisor — she did all the paperwork for her mother that died, but Vanguard is making her do it over again with their forms.”

He said Schwab seems to be attracting younger business owners and professionals.

For the growing number of American small-business owners and professionals with complex needs and $10 million or more invested, “it is very hard to keep the low-touch, low-fee Vanguard model” attractive, said Mike Topley, founder of $450 million-asset Lansing Street Advisors in Ambler, Pennsylvania.

“Investing is a psychology game, not an IQ game,” he said, and advisers’ role isn’t just to recommend Vanguard or other funds, but sometimes to talk clients out of buying an extra boat, or a shady private investment.

“Top client issues are care for elderly parents, parents supporting young adult children, addiction in families, and business exit planning. All four of these issues may lead to a period where you are talking to a client daily,” and that’s not what Vanguard is set up to do, Topley added.

Vanguard’s low fees remain “awesome,” and its role as an employer of over 10,000 at its headquarters is “lucky” for the region, Topley said. But nothing on Ramji’s watch, so far, has made it more attractive, he concluded.

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments