Amid controversy, Bahamian prime minister pledges direct payments to Cuban doctors

Published in News & Features

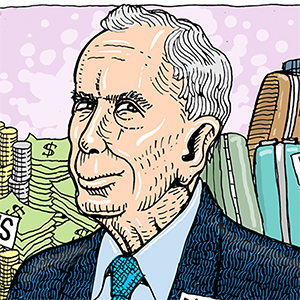

The prime minister of the Bahamas says his country is renegotiating an agreement to hire health care workers through Cuba’s official medical missions and that his government will pay all foreign workers directly, following a meeting with Secretary of State Marco Rubio this week.

“Anyone we hire, we’ll say, ‘Look, we have to pay you directly into your account,’” Prime Minister Philip Davis said on Wednesday in a press conference back from his trip to Washington.

The statement comes after the Miami Herald and The Tribune in The Bahamas reported on a purported agreement showing a Cuban state company was pocketing up to 92% of the money The Bahamas paid for the services of four Cuban health workers.

During the press conference, Davis, whose government refused to acknowledge the authenticity of the leaked contract, declined a request to publish The Bahamas’ contract with Cuba for medical services. “Well, they were published already, so why would we want to publicize them anymore?” he said.

“What I can say,” Davis added, “we are in the process of renegotiating all of these Memorandums of Understandings for labor out of Cuba, just as we are doing with other countries like the Philippines [from] where we have a number of foreign workers.”

Davis was among seven Caribbean prime ministers who met on Tuesday with Rubio, who addressed the issue of the Cuban medical brigades, among other U.S. concerns.

Rubio “reaffirmed our commitment to holding accountable Cuban regime officials, foreign government officials, and those involved in facilitating the regime’s forced labor scheme, including Cuba’s medical missions,” State Department spokesperson Tammy Bruce said.

During the discussions, several Caribbean leaders defended their use of Cuban health care workers, including doctors and nurses. They also continued to push back against Rubio’s assertions that foreign officials engaging in such contracts are participating in “forced labor” and would be subject to visa restrictions by the Trump administration.

“I think they were satisfied that we are not engaged in forced labor that we are aware of,” Davis said. “So if forced labor is occurring in our country with the Cubans, there is no evidence that we have come across.”

State Department human-trafficking reports and critics of Cuba’s medical brigades say Cuban health care workers not only do not receive their full salaries when hired by foreign governments, but their passports are also held, preventing them from being able to travel freely. Davis. acknowledged those are among several factors that could be perceived as “ingredients of forced labor.”

The Bahamas, he said, has spent the last few weeks identifying “ingredients of forced labor to see whether any of those are present in relation to any of the workers here in The Bahamas and if we discover that, that will be corrected.”

He cited a pre-independence example to argue that there was historical precedent for contracting foreign workers and paying their governments a portion of their salaries. He noted that before his country achieved independence from the British in 1973, many workers from The Bahamas and neighboring Turks and Caicos were hired in the United States to work as laborers under what was known as “The Contract” or “The Project.”

“All of my mother’s siblings, all of my father’s siblings, were all engaged under that regime called ‘The Contract,’ where part of their salaries were paid to the British government, and part was paid to them while they were in the United States. It was for them to collect when they came back to The Bahamas and they did not get [it] all back. That’s not an unknown concept and construct.

“But now that concept is being looked at as an ingredient of forced labor. So, we will address that,” he said.

Davis insisted that the amount Cuban health care workers were getting was not the issue, but that they are not getting all they are earning.

While the British government withheld part of the salaries under the arrangement that sent Bahamian laborers to fill gaps in the U.S. between 1943 to 1965, a portion was held in a savings fund, and another was sent to their families in the Bahamas, which is not the case with the Cuban health workers. The Cuban government has not disclosed how it uses the millions of dollars it receives as “fees” for the services of over 20,000 health workers around the world other than to say they are used to fund the public health system. But the critical state of the country’s hospitals and the chronic shortages of medicines suggest otherwise.

In The Bahamas case, an entity linked to the Cuban Ministry of Health was receiving $22,000 in monthly fees for the work of two medical advisors, a software engineer and a health data technician. In contrast, the four only received an “allowance” between $990 and $1,200 per month, according to a copy of the purported agreement published by the Miami-based group Cuba Archive.

Cuba Archive director Maria Werlau told the Herald that it is not enough for governments to pay doctors in these missions directly because, in the past, Cuban officials have pressured personnel in these brigades to transfer most of the money received in their personal bank accounts back to the Cuban government.

Davis said the question was put forward during the two-hour meeting with Rubio and two other State Department officials on whether the U.S. was barring them from “engaging with Cuban workers.”

“The answer was clearly, ‘No,’” he said. According to his recount of the meeting, U.S. officials responded that all they “are asking” is for Caribbean leaders to ensure they are not engaged in forced labor practices.

Davis and other Caribbean leaders called on U.S. officials to share any intelligence with them on forced labor and also spoke candidly about the challenges in providing health care throughout the Caribbean.

“Our nurses and our doctors are being recruited from our country by other countries,” he said.

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit at miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments