Faith leaders bear witness as migrants make their case in immigration court

Published in News & Features

LOS ANGELES -- Rev. Jason Cook, a minister at Tapestry, a Unitarian Universalist congregation, wore his traditional white collar and a colorful stole resembling stained glass when he arrived at immigration court in Santa Ana last Friday.

For several weeks, Cook and clergy members from a cross section of religions have been showing up at courtrooms in Orange County, Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego to stand with immigrants during their deportation hearings. The practice was launched after faith leaders learned that many immigrants seeking asylum were being whisked away by federal agents after what had been billed as routine court appearances, and locked up in remote detention facilities without a chance to prepare or say goodbye to family.

They have sought to use their presence to comfort migrants and lend a sense of moral authority to the proceedings. They have also taken to the courtroom benches to bear witness with silent prayer.

On Friday, clergy members roamed the courthouse halls in search of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. If plainclothes agents sat outside a courtroom, it was a good indication that the migrants inside had been targeted for expedited removal once their cases were heard.

Cook knows the presence of clergy won't necessarily change the outcome of the legal proceedings — though in at least one instance last month, ICE agents scattered when clergy showed up at a courthouse in San Diego. If nothing else, they hope to offer spiritual comfort, so the immigrants know they're not forgotten.

"There's a big piece of [our faith] that's about welcoming the stranger, about treating immigrants with compassion and care," Cook said. "We're there trying to appeal to a higher authority than ICE."

Many of the immigrants being detained at immigration court are asylum seekers who came into the country using the CBP One mobile app that the Biden administration had employed since early 2023 to create a more orderly process of applying for asylum. Migrants could use the app once they reached Mexican soil to schedule appointments with U.S. authorities at legal ports of entry to present their bids for asylum and provide biographical information for screening.

President Trump shut down the CBP One app hours after taking office in January. His administration has given ICE officials the power to quickly deport tens of thousands of immigrants who were granted legal entry to the U.S. for up to two years through the CBP One program, and is waging legal battles to roll back protections for hundreds of thousands of migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela who were granted temporary parole while seeking asylum.

Faith leaders say the work is an extension of their services for immigrants, who often attend their churches in sizable numbers. In the past, some places of worship have opened up their doors to shelter undocumented immigrants at risk of being deported. In L.A., faith leaders have organized food drives for immigrants afraid to leave their homes, as well as vigils and peaceful marches at the downtown Los Angeles federal building.

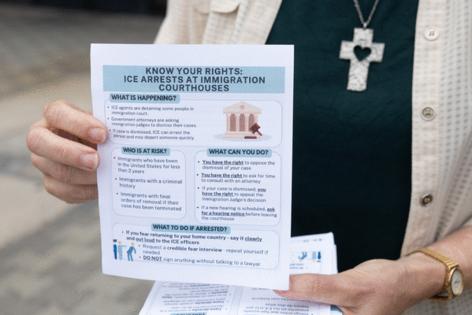

In the Inland Empire, clergy members have gone into grape fields to hand out "Know Your Rights" cards.

"Throughout history, across the world, clergy and faith leaders and spiritual leaders have played a really catalytic role in bending the arc toward moral justice," said Joseph Tomás Mckellar, executive director of PICO California, the largest faith-based community organizing network in the state. "When they do it right, they leave space for others to walk the walk, as well."

On June 11, the Catholic Diocese of San Diego reached out to area clergy to ask for help in expanding efforts to accompany migrants to their hearings.

Father Scott Santarosa, of Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish, said the letter garnered so much interest, they had to limit the number of clergy who could attend. That Friday, which also coincided with World Refugee Day, they held a Mass before arriving at immigration court.

"We weren't planning to block or get in the way or do anything to disrupt. We just planned to be present and observe and say with our presence to migrants and refugees, 'Hey, you're not alone,'" he said.

One Venezuelan asylum seeker, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution if she is deported back to her home country, had a hearing scheduled in L.A. County in early June with her children. She arrived in the U.S. in December after entering through the CBP One app. The June hearing would be her first.

She knew she was at risk of deportation and wondered whether to attend her hearing. She shared her fears with an area pastor, who offered to go with her. On the morning of her hearing, she arrived at court accompanied by three pastors and a translator. She felt protected, she said, when the judge granted a future court hearing and she was allowed to leave.

"Everything went well," she said. "I feel as if it was because of the Christian support that I had at that moment."

Cook, the Unitarian Universalist minister in Orange County, said he attends court at least twice a week.

Initially, ICE agents seemed averse to confronting religious leaders, and in some cases, left the courthouse when clergy members arrived.

But over time, Cook said, the agents have gotten more confrontational, telling clergy they must stay 10 feet away from agents. He said he watched one ICE agent push a clergy member against the wall after she tried to escort an immigrant out of court.

They have carried on, he said, because the work feels important and aligned with their mission of faith.

"What we are is conscience on display for these folks, and if that triggers shame or reflection, that's a good thing," Cook said outside a courtroom, not far from ICE agents.

Dave Gibbons, founder of the Newsong Church in Santa Ana, said he took a break from court visits after a Central American couple he was escorting got pulled away and detained in front of their child. He broke down in tears recounting the episode for his congregation. But he was determined to return.

"We believe it's at the heart of the gospel," Gibbons said. "There's nothing more sacred than standing alongside those being marginalized."

Rev. Terry LePage, a community minister in Orange County, has attended immigration hearings nearly daily. She spent Friday morning handing out fliers that notified migrants headed to hearings of their rights and warning that ICE agents were present.

That morning, clergy members encountered a Haitian man who had been granted temporary protected status during the Biden administration. He arrived for his asylum hearing without an attorney. He wore a crisp white shirt and carried his documents in a black case.

Clergy leaders urged him to contact his family and let them know that he might be detained. But the man, who spoke Spanish, was sure he would be allowed to return home.

Inside the courtroom, a Department of Homeland Security attorney argued that the man's case should be dismissed, a request the judge granted despite the migrant's pleas. Seated in the audience, Thomas Crisp, an Orange County chaplain, watched in dismay and offered a few last words of comfort: "May God bless you."

The Haitian man made it two steps out of the courtroom before he was swarmed by federal agents and ushered down an emergency exit stairwell.

____

This article is part of The Times' equity reporting initiative, funded by the James Irvine Foundation, exploring the challenges facing low-income workers and the efforts being made to address California's economic divide.

____

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments