Best shot to save Florida reefs? An industrial factory making heat-hardy babies

Published in News & Features

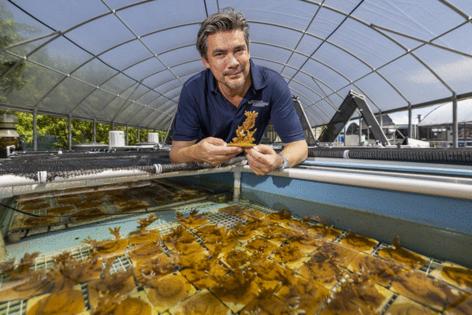

MIAMI -- When Andrew Baker looks out at the vacant lot next to his office on Virginia Key, he doesn’t see the trees or grass that are there now. He sees a factory of the future. One story tall, roughly the size of half a football field. A high-efficiency production line designed not for electronics or auto parts — but for coral.

Such a facility would be unprecedented leap forward in reef restoration. Within four or five years, it could be up and running, as most of the necessary scientific foundation has already been developed and the work force is already being trained. With the help of automation, robots, and IVF-style breeding, it could produce hundreds of thousands of selectively bred specimens a year to help construct living reefs resistant to the rising temperatures killing off corals across the globe.

“These are some renderings,” Baker, a marine biologist at the University of Miami, said, opening a design he created with AI. A sleek facility with dozens of water tanks, where almost every stage of coral life, from conception to adulthood, would be engineered and optimized.

A fully industrialized coral factory may sound far-fetched to some, but it might be the last hope for the world’s reefs, including the 350-mile-long formation of brain, staghorn and fan coral that forms a natural sea wall off South Florida, Baker said. “We’ve done the science to show we can scale it up, but until we do it, we’ll fail to meet the challenge of this global problem.”

It would represent a major shift in approach, and a far more aggressive intervention than anything that’s been done before. But since relentless heat waves and environmental assault have killed 9 in 10 coral since the 1970s and keep thwarting more traditional ways to restore reefs, some scientists believe anything less would amount to surrender.

“If we fail to take action at the scale that’s needed to give Florida’s coral reef an opportunity to survive climate change, then we’re going to lose that ecosystem and it’ll cease to be part of Florida’s identity,” Baker said. Also lost will be the billions of dollars coral reefs contribute to the local economy, from drawing tourism to fisheries and coastal protection from hurricanes.

Right now, nobody has stepped up to bankroll such an ambitious effort. But the Department of Defense and Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection have already spent millions to support research on this type of next-generation reef-building, and Baker and other marine scientists believe private investments or taxpayer backing could make it a reality.

The techniques and technology are already proven. On a recent evening, in a lab at UM’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science along the Rickenbacker Causeway, one crucial step toward mass production of reef-building material was already under way: The breeding of a stock of climate-hardy corals.

Getting the product right

For a single coral to exist is nothing short of a lottery win. In the oceans, adult brain corals like the one in Baker’s lab release bundles of both sperm and eggs that float to the surface, split apart, and drift on currents until they meet and fuse with a mate. If luck holds, the then free-floating embryo develops into a larvae, which settles on a reef and begins life as a coral polyp.

Given the vastness of the ocean and the microscopic size of coral sperm and eggs, the odds of making it are vanishingly small. To improve their chances, corals have learned to spawn in synchronized waves, with each species tuned to a specific phase of the moon – nature’s shared calendar.

Despite this remarkable orchestration, even if a single polyp comes out of the hundreds of thousands of bundles a single coral can produce, it’d be considered an evolutionary success.

A floor above Baker’s office, in a room the size of a large walk-in closet, the odds are far better – especially if PhD candidate Katherine Hardy and her colleagues lend a helping hand.

Inside four tanks, each about the size you might find at a dentist’s office, temperature and salinity are carefully controlled to mimic the ocean. A handful of snails, shrimp, and fake moonlight add to create the perfect matrix – an illusion of nature, all created by marine biologists to get coral to release their precious bundles.

That recent night, the scientists joked that their playlist of romance-themed songs ranging from the Police’s “Roxanne” to Frank Sinatra’s “Fly me to the Moon” helped serenade the first brain coral into releasing a shy drizzle of white bundles that floated to the top of a funnel-shaped net. Other corals saw no need to pace themselves and followed much faster. It was a beautiful sight, like the spawning events in nature documentaries showing the magic and wonder of nature.

And yet the sight isn’t entirely natural, not just because the corals are in tanks, but because some of them are nearly 900 miles from their home in Honduras, from a region where ocean temperatures are about 2 degrees higher than in southern Florida. That type of heat has killed all but the most battle-hardened survivors in Florida. Yet in Honduras, the corals are still thriving, Hardy explained as she carefully pulled out the nets and transferred the Honduran bundles into Pyrex containers.

Changing gears

Until now, the global strategy to save reefs has largely relied on growing fragments in nurseries and having divers painstakingly plant them back into the ocean. Each year, thousands of volunteers outplant tens of thousands of corals, only to watch restoration fall hopelessly behind the pace of destruction. On top of that, the newly planted coral are sourced from a rapidly shrinking genetic pool.

Without transitioning to cleaner energy, scientists give the world’s reefs some 25 years before complete collapse. That’d be a devastating blow to Florida, where reefs have been protecting coastal cities like Miami by absorbing 97 percent of wave energy. Without corals, the US economy is expected to suffer an average of $1.8 billion in flood-related damages each year.

By breeding Florida’s hardened survivors with Honduran corals, the scientists hope to create offspring that will carry a new heat-resistant genetic armor for the climate battles ahead.

Once the spawning ends, the team turns off the music and takes the Pyrex containers into a room where the temperature is kept at around 82 degrees. Here, Hardy and her colleagues mix the Honduran and Floridian bundles, with sperm and eggs of each fertilizing the other.

“This is the first Flonduran brain coral ever produced,” Baker commented. “It’s a world first.” Scientists call this process “assisted gene flow,” a way to supercharge evolution.

During their 500 million years on the planet, coral proved that they’re masters of adaptation. Whether facing global warming that turned large swaths of land into deserts or cooling that killed off the dinosaurs, coral evolved. They survived.

Those past periods of global changes in the planet’s climate, no matter how dramatic, unfolded over millennia. Coral had thousands of generations to adapt and evolve. Today’s heating, driven by fossil fuel emissions, is unfolding within just a few decades. Neither coral nor any other species are afforded the time to adapt.

That’s why scientists are working to supercharge evolution. The Flonduran brain coral, they hope, might survive even as the temperatures off Florida’s coast will more closely resemble those of continental Honduras.

Ramping up the coral production line

While newly crossbred corals were recently outplanted and are now being monitored to evaluate which combination should go into production, researchers are racing to get the assembly line ready to scale output.

The goal is to run at near year-round capacity, with different coral spawning at different times during the year, not just over the couple of months in summer when they’d all spawn naturally. That was unthinkable in the past, when sperm and eggs could only be collected during night dives or from fragments that had to be broken off a reef and placed in a lab shortly before they’d spawn.

In 2017, however, a group of European scientists described the first-ever successful protocol that allowed “coral husbandry,” including by using special lights to mimic the sun and moon, and, effectively, trick coral into spawning outside the ocean.

Joana Figueiredo, a professor at Nova Southeastern University’s Marine Larval Ecology and Recruitment Laboratory, immediately saw the potential. “It opened a lot of opportunities,” said Figueiredo, who has a background in aquaculture.

Figueiredo, who also directs the National Coral Reef Institute, realized that coral could now be farmed in controlled environments – not dissimilar from the shrimp she’d worked with during her doctoral studies in Portugal. “And since we already had the tanks, all we needed was the lights.”

The dozens of baby coral in Figueiredo’s windowless lab on Dania Beach are now illuminated by cornflower blue light that mimics the sun at night and the moon in the middle of the day. With that, the researchers can trick the coral into spawning during the day, a more labor-friendly time to tend to their needs.

Already, the different coral at Nova Southeastern spawn thrice a year. That alone makes the entire operation more efficient: With staggered cycles, researchers can move coral at different stages of growth through the production line, tripling the output. “It’s a much more cost effective use of space and equipment,” Figueiredo said.

Printing coral

Automation promises to be the next key. A coral printer, Baker said, would be great.

Instead of ink or plastic, the printer would dispense a mix of hydrogel and coral larvae, placed at just the right distance to give each the necessary space to grow. That way, 1,000 larvae could grow on a tile not much larger than a coaster.

After about two months, a robot could break off each and place them onto larger tiles, where the coral would grow for another four to seven months, until they’re sturdy enough to be taken to real reefs. “This kind of thing does happen in industrial manufacturing processes,” Baker said.

Advanced printing technology also could potentially preempt the leading cause of coral death: starvation. When waters overheat, the microscopic algae living inside coral stop producing sugar – the coral’s food source – and instead release toxins.

As the coral understands that it’s being poisoned from within, it expels the algae in a desperate act of self-preservation, turning ghostly white in the process. The coral, now bleached, is alive, but slowly starving. Just like coral themselves, however, some algae are already more heat-resistant than others, and a printer could inject this superior algae in hydrogel alongside the coral larvae, ensuring that the best is available from the beginning.

Paying the bills

With her background in aquaculture, which produces more than half of the fish consumed globally, Nova Southeastern’s Figueiredo sees the massive potential in the coral factory concept. Though the new approach will resemble factory farming, the potential benefits to humans are infinitely greater than an affordable salmon steak.

Private enterprise could grow the coral and plant them on artificial reefs, Figueiredo said — a nature-based barrier to protect from storm surge. Unlike a concrete wall, such as the 20-feet high one the Army Corps of Engineers had suggested, reefs also restore themselves. “I wouldn’t see why that couldn’t be done,” she said of private-owned reefs.

Given that reeds can be seen as public infrastructure that can protect the entire coast, taxpayer funding is another option. The Department of Defense, for one, recognized the value. That’s in part because of Hurricane Michael. In 2018, the Cat 5 destroyed or demolished 484 buildings at the Panhandle’s Tyndall Air Force Base beyond repair. For the recovery, the DoD is spending an estimate of about $5 billion.

Compared to that, the $50 million the DoD granted to universities like UM to create artificial reefs populated with heat resistant coral and oysters was peanuts. An ounce of of prevention is worth a cure, Baker said. “It might cost us millions of US dollars to have an industrial-scale center, but it will cost us billions in the future if we don’t.”

Whether publicly or privately funded, the numbers the researchers are talking about are staggering. The hundreds of thousands of corals that Baker envisions producing would simply cover the needs of Miami-Dade. Additional factories could be built to supply the Keys, Hawaii, the Bahamas, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

At Nova Southeastern, Figueiredo has already set up a program that trains the new work force that will be needed to staff and run them. So far, she’s trained more than 50 people in setting up facilities to sexually propagate corals.

Some skeptics might argue that coral factories are only slightly more realistic than Baker’s childhood fantasies of becoming a dinosaur. Baker, now salt-and-pepper-haired, disagrees. The technology is available, and the situation has long been dire enough to force extreme action. With the right investment, the first factory could be up-and-running in as little as four years.

The time is now, he said. “It’s not sci-fi.”

____

This climate report is funded by Florida International University, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the David and Christina Martin Family Foundation in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners. The Miami Herald retains editorial control of all content.

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit at miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments