Commentary: Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu don't have the same goals

Published in Op Eds

When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Donald Trump met at the White House in early July for the third time this year, the two men were all smiles. Trump heaped praise on the Israeli premier (and himself) for a job well done on Iran, insisting yet again that the U.S. and Israeli airstrikes against Tehran’s nuclear facilities left its program “obliterated.” Netanyahu thanked Washington for its extensive support and gifted him a letter that nominated Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize.

But things have changed in the three weeks since. And while the relationship between Trump and Netanyahu isn’t at a breaking point, the two appear to hold aspirations for the Middle East that are increasingly hard to square with each other.

The 21-month war in Gaza is, of course, the most dominant issue affecting the partnership. Trump ostensibly wants to get it solved. He’s tired of the killing and the bad press, has been pining about brokering an agreement between Israel and Hamas even before he won the election in November and increasingly sees the conflict as a morass. “A lot of hate, long-term hate,” Trump told reporters during his confab with Netanyahu on July 7, “but we think we’re going to have it solved pretty soon, hopefully with a real solution, a solution that’s going to be holding up.”

Yet in the weeks since Trump made those comments, the possibility of a ceasefire and hostage release deal has moved only a few inches toward the finish line. The three big issues preventing Israel and Hamas from signing a deal — whether a 60-day truce will lead to a permanent end to the war, how extensive the Israeli military withdrawal in Gaza will be during that pause and how humanitarian aid will be distributed to Palestinians — remain unsolved. While the Israelis have reportedly agreed to move troops farther away from key corridors, some question if Israeli diplomats shuttling to Qatar and Egypt for talks actually have the mandate to negotiate.

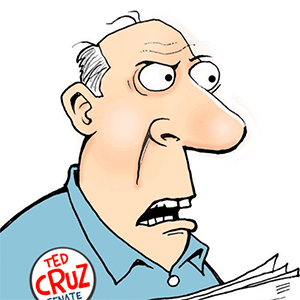

Netanyahu is highly protective of the process and beholden to ultranationalists in his cabinet who equate any deal with Hamas with shameful surrender, and he has trumpeted Hamas’ defeat so many times that any walk-back from this position will have political repercussions for him.

The Israel Defense Forces are also in the process of expanding their ground offensive in Gaza to Deir al-Balah, a city Israeli troops haven’t entered because some of the 20 Israeli hostages still alive are thought be located there. An Israeli incursion into Deir al-Balah could either increase the pressure on Hamas to make a deal on Israel’s terms or push the group further away from the process. The second scenario would produce a longer war, more deaths and a greater likelihood of more highly publicized incidents — such as the shelling of Gaza’s only Catholic Church, which caused Trump to phone Netanyahu in a rage.

Gaza may be on everybody’s mind, but the elephant in the room is what to do about Syria. Although the United States and Israel both claim to want peace, security and stability in a country whose nearly 14-year civil war ended in December, the two states aren’t playing by the same set of rules and don’t even share the same goals.

If last week’s violence between Druze and Bedouin militias, as well as Israel’s intervention in the fighting, tell us anything, it’s that Netanyahu views the new rulers in Damascus as no better than Bashar Assad, the despot whose half-century family rule ended abruptly in December.

Ahmad al-Sharaa, Syria’s interim president, may have traded his gun for a Western-style suit as he hobnobs with Arab leaders in the hope of attracting foreign investment. But to the Israeli security establishment, al-Sharaa is the same jihadist the U.S. military once detained in Iraq more than two decades ago. Some Israeli ministers have referred to al-Sharaa and the new post-Assad government he commands as a wolves in sheep’s clothing, in which Sunni supremacism and sectarianism rule the day.

“Bottom line: In al-Sharaa’s Syria, it is very dangerous to be a member of a minority — Kurd, Druze, Alawite, or Christian,” Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar wrote on X over the weekend.

The Trump administration takes a different approach. Trump has invested a lot in al-Sharaa, seeing the former jihadist fighter-turned-politician as somebody who can pull Syria out of the doldrums of despair. During his trip to Saudi Arabia in the spring, Trump met al-Sharaa, shook his hand and marveled afterward that the 40-something was a tough, impressive guy with the opportunity to bring his country out of the wilderness. In a big sign of good faith, Trump ordered the removal and suspension of U.S. sanctions on Syria.

So the White House wasn’t pleased when Israeli aircraft started dropping bombs on Syrian troops who were dispatched to the southern Syrian province of Sweida to quell the fighting between the Druze and Bedouins. Israel assessed al-Sharaa’s army was actually targeting the Druze population; Washington, however, hasn’t bought into this claim and argues the Syrian government is doing the best it can under a difficult situation. One White House official blasted Netanyahu for acting like “a madman” whose default tool to solve a problem is dropping bombs. Meanwhile, the State Department stressed that Washington didn’t support Israel’s military intervention in southern Syria.

These two perspectives are destined for a clash. Whether Trump stands up for his own policy or defers to Netanyahu’s supposed judgment will determine if he’s the visionary he frequently wants to be or is merely a supplicant.

____

Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist for the Chicago Tribune.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments