Commentary: Jim Crow meets ICE at 'Alligator Alcatraz'

Published in Op Eds

A few years ago I came across a profoundly unnerving historical photo: A lineup of terrified, naked Black babies cowered over the title “Alligator Bait.” As it turned out, the idea of Black babies being used as alligator bait was a beloved trope dating back to the antebellum South, though it didn’t really take off until after the Civil War.

The image I saw was created in 1897, just one year after Plessy vs. Ferguson established “separate but equal” as the foundational doublespeak of segregation. With formerly enslaved people striking out and settling their own homesteads, the prevailing stereotypes deployed to justify violence against Black people were forced to evolve. We were no longer simple and primitive, in desperate need of the civilizing stewardship of white Christian slave owners. After emancipation, we became dangerous, lazy and worthless.

Worth less, in fact, than the chickens more commonly used to bait alligators.

White Floridians in particular so fell in love with the concept of alligators hungry for Black babies that it birthed an entire industry. Visitors to the Sunshine State could purchase souvenir postcards featuring illustrations of googly-eyed alligators chasing crying Black children. There was a popular brand of licorice called “Little African,” with packaging that featured a cartoon alligator tugging playfully at a Black infant’s rag diaper. The tagline read: “A Dainty Morsel.” Anglers could buy fishing lures molded in the shape of a Black baby protruding from an alligator’s mouth. You get the idea.

When I first learned of all this, naturally, I was unmoored. I was also surprised that I’d never heard of the alligator bait slur. Why doesn’t it sit alongside the minstrel, the mammy and the golliwog in our cultural memory of racist archetypes? Did it cross some unspoken line with the vulgarity of its violence? Perhaps this particular dog whistle was a tad too audible?

Or was it plausible deniability? Did people (including historians) wave it away because babies were never “really” used as alligator bait? It’s true that beyond the cultural ephemera — which includes songs (such as the ragtime tune “Mammy’s Little Alligator Bait”) and mechanical alligator toys that swallow Black babies whole, over and over again — there are apparently no surviving records of Black babies sacrificed in this way. No autopsy reports, no court records proving that anyone was apprehended and convicted of said crime.

But of course, why would there be?

The thing I found so unnerving about the alligator bait phenomenon wasn’t its literal veracity. There’s no question human beings are capable of that and far worse. Without a doubt, “civilized” people could find satisfaction — or comfort, or justice, or opportunity — in the violent slaughter of babies. Donald Trump’s recently posted AI clip “Trump Gaza,” which suggests the real world annihilation of Palestinians will give way to luxury beachfront resorts, is a shining example. The thing that haunted me about alligator bait was the glee with which the idea was embraced. It was funny. Cute. Harmless. Can’t you take a joke?

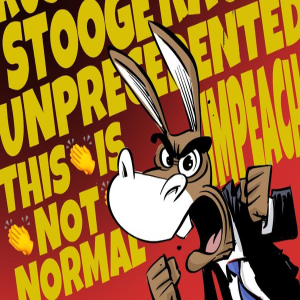

Now here we are, 100 years after “Mammy’s Little Alligator Bait,” and the bigots are once again using cartoon alligators to meme-ify racial violence, this time against immigrants. Just like the title “Alligator Bait,” the Florida detention center name “Alligator Alcatraz” serves multiple ends: It provokes sadistic yuks. It mocks. It threatens. But most crucially, it dehumanizes. “Alligator Bait” suggests that Black people are worthless. By evoking the country’s most infamous prison, “Alligator Alcatraz” frames the conversation as one about keeping Americans safe. It suggests the people imprisoned there are not vulnerable and defenseless men and women; anyone sent to “Alligator Alcatraz” must be a criminal of the worst sort. Unworthy of basic human rights. Fully deserving of every indignity inflicted upon them.

“Alligator Alcatraz” cloaks cruelty in bureaucratic euphemism. It’s doublespeak, masking an agenda to galvanize a bloodthirsty base and make state violence sound reasonable, even necessary. It has nothing to do with keeping Americans safe. Oft-cited studies from Stanford, the Libertarian Cato Institute, the New York Times and others have shown conclusively that immigrants, those here legally and illegally, are significantly less likely to commit violent crimes than their U.S.-born neighbors.

If those behind “Alligator Alcatraz” cared at all about keeping Americans safe, they wouldn’t have just pushed a budget bill that obliterates our access to healthcare, environmental protection and food safety. If they actually cherished the rule of law, they would not deny immigrants their constitutionally guaranteed right to due process. If they were truly concerned about crime, there wouldn’t be a felon in the White House.

As souvenir shops and Etsy stores flood with “Alligator Alcatraz” merch, it’s worth noting that none of it is played for horror. Like the cutesy alligator bait merchandise before it, these aren’t monster-movie creatures with blazing eyes and razor-sharp, blood-dripping teeth. The “Alligator Alcatraz” storefront is cartoon gators slyly winking at us from under red baseball caps: It’s just a joke, and you’re in on it.

And it’s exactly this cheeky, palatable, available-in-child-sizes commodification that exposes the true horror for those it targets: There will be no empathy, no change of heart, no seeing of the light. Dear immigrants of America: Your pain is our amusement.

The thing I keep wondering is, would this cheekiness even be possible if everyone knew the alligator bait history, the nastiness of which was buried so deep that “Gator bait” chants echoed through the University of Florida stadium until 2020? Would they still chuckle if they saw the century-old postcards circulated by people who “just didn’t know any better”? My cynical side says: Yeah, probably. But my strategic side reminds me: If history truly didn’t matter, it wouldn’t be continuously minimized, rewritten, whitewashed.

There’s truth in the old idiom: Knowledge is power. Anyone trying to keep knowledge from you, whether by banning books, gutting classrooms, denying identities or burying facts, is only trying to disempower you. That’s why history, as painful as it often is, matters.

Remembering the horror of alligator bait isn’t about dwelling on the grotesque. It’s about recognizing how cruelty gets coded into culture. “Alligator Alcatraz” is proof that alligator bait never went away. It didn’t evolve or get slicker. It’s the same old, tired cruelty, rebranded and aimed at a new target.

The goal is exactly the same: to manufacture consent for suffering and ensure the most vulnerable among us know where they stand — as props, as bait, as punchlines. And no joke is more vulgar than one mocking the pain of your neighbors, whether they were born in this country or not.

____

Ezra Claytan Daniels is a screenwriter and graphic novelist whose upcoming horror graphic novel, “Mama Came Callin’,” confronts the legacy of the alligator bait trope.

_____

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments