Can Democrats retake the US House? It could depend on Florida

Published in Political News

In their bid to retake the U.S. House of Representatives, Democrats hold a strong hand this election.

They don’t occupy the White House, which in a midterm election year typically means they’ll win more seats than lose. They need only to overcome a razor-thin deficit of 218-214 in the chamber. Most importantly, poll numbers show President Donald Trump at historic lows.

And yet whether Democrats regain the House for the first time since 2022 may hinge on a handful of Florida congressional districts.

Some state Republicans are pushing for a rare mid-decade redrawing of congressional boundaries. That could put seats long held by Democrats — including those now held by Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Darren Soto, Jared Moskowitz and Tampa Bay’s own Kathy Castor — up for grabs.

Far beyond the state’s borders, Democrats like U.S. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries of New York said his party is concerned enough that it is already responding.

“We are going to operate with an all-hands-on-deck approach to push back against this Republican scheme,” Jeffries told the Tampa Bay Times this week. “We’ll make sure that the values of Florida voters are vindicated as we push back against this politically biased effort.”

Florida joins the fray

State lawmakers typically redraw boundaries for legislative and congressional districts every 10 years. That timetable is driven by the U.S. census, which provides precise demographic information once a decade.

Consultants crunch the data and advise lawmakers on how best to draw the districts. In theory, this advice is meant to enhance equal representation. In practice, this advice is used to favor one party over another.

In Florida, voters in 2010 passed a constitutional amendment called Fair Districts that forbids lawmakers from drawing district boundaries for political purposes. Its intent was upheld in a series of legal challenges to the Legislature’s redistricting in 2012.

Voting rights groups like the League of Women Voters and Common Cause say Florida law is clear: No gerrymandering is allowed. They are calling lawmakers and conducting voter outreach to raise awareness that this could happen.

“It might be fine in Texas,” said Amy Keith, Florida state director of Common Cause, a left-leaning advocacy group, referencing new congressional maps drawn by Republicans in that state last summer. “But we know that’s not allowed in Florida.”

The new maps in Texas, which had been requested by President Donald Trump, set off a chain reaction elsewhere in the country. California and Virginia lawmakers were among those who retaliated by redrawing districts to help Democrats. Missouri and North Carolina lawmakers were among those who responded with redrawn districts further favoring Republicans.

It wasn’t until December that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced that he would push to redraw districts in his state. In January, he called for a special session for April 20-24.

DeSantis said he scheduled it in April because he expected a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling. The court is expected to rule on a complex legal dispute in Louisiana on whether congressional districts can be drawn by using race as a factor. If the court’s conservative minority finds that method unconstitutional, it would deliver a fatal blow to the Voting Rights Act that sought to protect the rights of minorities. Such a decision would also have far-reaching implications on redistricting across the nation, including Florida.

While calling a special session is easy, getting lawmakers to do anything is another matter. Florida House Republicans, who assembled a redistricting committee last summer, have been frustrated by the slower pace set by DeSantis. Senate Republicans are lagging behind. They haven’t come up with any maps. President Ben Albritton cautioned lawmakers about the significant litigation that can follow redistricting.

“Senators should take care to insulate themselves from partisan-funded organizations and other interests that may intentionally or unintentionally attempt to inappropriately influence a potential mid-decade redistricting process,” Albritton warned in a memo last month.

Yet it’s not lawsuits that pose the biggest risk for Republicans if they choose to go ahead with redistricting.

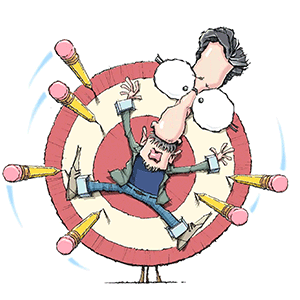

Is this ‘dummymandering’?

This latest round of redistricting could mean that Republicans ditch an approach they’ve followed for more than 30 years of packing progressives into urban districts.

That approach drains Democratic voters from neighboring, more suburban districts, making them redder. This strategy has helped give the GOP a 20-8 edge in Florida’s congressional delegation.

But if Republicans are to find more seats this year to preserve control of the U.S. House, they would need to crack open those urban districts by dispersing the Democratic majorities into neighboring districts held by Republicans.

Republicans think they can win these more competitive seats because of their numerical advantage with registered voters. As of January, Republicans boast a statewide edge of nearly 1.5 million voters.

Still, even with that going for them, the net effect of the redrawn districts would make all of the districts competitive. Put another way, by attempting to capture the Democratic strongholds, Republicans risk diluting the conservative vote in the districts they usually win.

It’s not an issue that incumbent congressional Republicans facing reelection are eager to talk about. Rep. Ana Paulina Luna, whose Pinellas County district covers parts of St. Petersburg and Clearwater, would face a tougher reelection battle if voters from Castor’s neighboring Democratic-majority district were to be suddenly included. Through a campaign spokesperson, Luna declined to comment.

Ultimately, if they go ahead with redistricting, Republicans would want to avoid what Democrats did in 1992 when they held the majority in Florida. They drew new districts that created minority-majority districts that led to the state’s first elected Black U.S. representatives since Reconstruction. Within four years, however, they lost both the Florida Senate and House because the new districts essentially “bleached” the many more remaining districts, making them much more winnable for Republicans.

Given recent surprise wins by Democrats in special elections in Trump-controlled districts in Texas and Louisiana, Jeffries said Republicans could be overplaying their hand this time around, a redistricting self-own called “dummymandering.”

“It’s a huge gamble,” Jeffries said. “They’ll put Republican candidates in jeopardy of losing more seats as a result of the dummymander.”

Still, Jeffries and voting rights groups point to broad public opposition to gerrymandering and say they’d rather Republicans avoid the redistricting fight altogether.

“We should expect our lawmakers to follow the (state) constitution,” said Jessica Lowe-Minor, president of the League of Women Voters of Florida. “No matter where lawmakers are on the political spectrum, they shouldn’t support the gamesmanship of rewriting the rules to suit themselves.”

©2026 Tampa Bay Times. Visit at tampabay.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments