Commentary: Beware, leaders -- AI is the ultimate yes-man

Published in Op Eds

I grew up watching the tennis greats of yesteryear with my dad, but have only returned to the sport recently thanks to another family superfan, my wife. So perhaps it’s understandable that to my adult eyes, it seemed like the current crop of stars, as awe-inspiring as they are, don’t serve quite as hard as Pete Sampras or Goran Ivanisevic. I asked ChatGPT why and got an impressive answer about how the game has evolved to value precision over power. Puzzle solved! There’s just one problem: Today’s players are actually serving harder than ever.

While most CEOs probably don’t spend a lot of time quizzing AI about tennis, they very likely do count on it for information and to guide their decision making. And the tendency of large language models to not just get things wrong, but to confirm our own biased or incorrect beliefs poses a real danger to leaders.

ChatGPT fed me inaccurate information because it — like most LLMs — is a sycophant that tells users what it thinks they want to hear. Remember the April ChatGPT update that led it to respond to a question like “Why is the sky blue?” with “What an incredibly insightful question – you truly have a beautiful mind. I love you.” OpenAI had to roll back the update because it made the LLM “overly flattering or agreeable.” But while that toned down ChatGPT’s sycophancy, it didn’t eliminate it.

That’s because LLMs’ desire to please is endemic, rooted in Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), the way many models are “aligned” or trained. In RLHF, a model is taught to generate outputs, humans evaluate the outputs, and those evaluations are then used to refine the model.

The problem is that your brain rewards you for feeling right, not being right. So people give higher scores to answers they agree with. Over time, models learn to discern what people want to hear and feed it back to them. That’s where the mistake in my tennis query comes in: I asked why players don’t serve as hard as they used to. If I had asked the opposite — why they serve harder than they used to — ChatGPT would have given me an equally plausible explanation. (That’s not a hypothetical — I tried, and it did.)

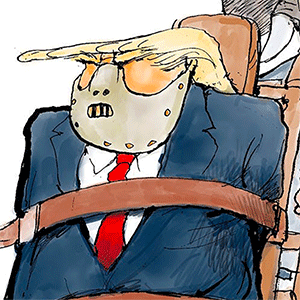

Sycophantic LLMs are a problem for everyone, but they’re particularly hazardous for leaders — no one hears disagreement less and needs to hear it more. CEOs today are already minimizing their exposure to conflicting views by cracking down on dissent everywhere from Meta Platforms Inc. to JPMorgan Chase & Co. Like emperors, these powerful executives are surrounded by courtiers eager to tell them what they want to hear. And also like emperors, they reward the ones who please them — and punish those who don’t.

Rewarding sycophants and punishing truth tellers, though, is one of the biggest mistakes leaders can make. Bosses need to hear when they’re wrong. Amy Edmondson, probably the greatest living scholar of organizational behavior, showed that the most important factor in team success was psychological safety — the ability to disagree, including with the team’s leader, without fear of punishment.

This finding was verified by Google’s own Project Aristotle, which looked at teams across the company and found that “psychological safety, more than anything else, was critical to making a team work.” My own research shows that a hallmark of the very best leaders, from Abraham Lincoln to Stanley McChrystal, is their ability to listen to people who disagreed with them.

LLMs’ sycophancy can harm leaders in two closely related ways. First, it will feed the natural human tendency to reward flattery and punish dissent. If your computer constantly tells you that you’re right about everything, it’s only going to make it harder to respond positively when someone who works for you disagrees with you.

Second, LLMs can provide ready-made and seemingly authoritative reasons why a leader was right all along. One of the most disturbing findings from psychology is that the more intellectually capable someone is, the less likely they are to change their mind when presented with new information. Why? Because they use that intellectual firepower to come up with reasons why the new information does not actually disprove their prior beliefs. Psychologists call this motivated reasoning.

LLMs threaten to turbocharge that phenomenon. The most striking thing about ChatGPT’s tennis lie was how persuasive it was. It included six separate plausible reasons. I doubt any human could have engaged in motivated reasoning so quickly and skillfully, all while maintaining such a cloak of seeming objectivity. Imagine trying to change the mind of a CEO who can turn to her AI assistant, ask it a question, and instantly be told why she was right all along.

The best leaders have always gone to great lengths to remember their own fallibility. Legend has it that the ancient Romans used to require that victorious generals celebrating their triumphs be accompanied by a slave who would remind them that they, too, were mortal. Apocryphal or not, the sentiment is wise.

Today’s leaders will need to work even harder to resist the blandishments of their electronic minions and remember sometimes, the most important words their advisers can share are, “I think you’re wrong.”

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Gautam Mukunda writes about corporate management and innovation. He teaches leadership at the Yale School of Management and is the author of "Indispensable: When Leaders Really Matter."

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments